Research

Oak pollen grains and acorns – long and short distance travellers

Consider an oak tree that grew naturally from an acorn in a forest. It has two parents, a ‘mother’ and a ‘father’. Assuming they are still alive, the mother is likely to be growing nearby, because acorns are large and unlikely to travel far. The father could be much more distant because oak pollen is dispersed by the wind and can be carried considerable distances.

Dispersal of acorns was particularly important when the last glaciation ended. All oaks had been eliminated from northern Europe, but as the climate warmed and the ice sheets retreated, it was possible for both Quercus robur and Quercus petraea to recolonise from their southerly refugia in the Iberian and Italian peninsulas. This would have happened at just a few metres per oak generation without help from birds and mammals, especially scatter-hoarders that bury acorns singly or in small caches over a wide area for future retrieval. A significant proportion of the buried acorns are never retrieved so are able to go on to germinate.

Studies of acorn dispersal have shown in Europe it is the jay (Garrulus glandarius) that disperses most acorns. A single jay is capable of burying as many as 4,600 in a single season over a wide area. Up to nine acorns can be carried simultaneously in the jay’s bill and oesophagus, over distances as great as 8 kilometres from the mother tree.

Of the two white oak species in northern Europe, jays disperse Quercus robur (pedunculate oak) more effectively than Quercus petraea (sessile oak). There are various reasons for this:

- Jays prefer long slim acorns which are easier to swallow. Q. robur acorns are longer and slimmer than those of Q. petraea.

- Jays collect acorns in September and October when they are still hanging on the tree. The long peduncles of Q. robur make the acorns more conspicuous so they are more likely to be collected.

- Oaks growing at forest margins and in open areas are likely to produce greater numbers of acorns and start producing them at a younger age. Q. robur is more likely to be found in these habitats than Q. petraea.

Because of these differences, we can expect Q. robur to have recolonised northern Europe ahead of Q. petraea. There is evidence for Q. robur having arrived in southern Scandinavia about 8500 years ago but Q. petraea not until 4000 years ago. A pollen study in Norfolk has suggested that Q. petraea arrived 700 years later than Q. robur.

DNA analysis now allows the travels of oak pollen to be investigated. In one study, 35% of acorns sampled in an isolated patch of Q. robur forest east of the Ural Mountains were found to be the result of fertilisation by pollen from outside this forest1. The nearest other Q. robur trees were 35 kilometres away in another small forest, but this was not the source of most of the pollen. The next nearest source was over 80 kilometres away. It is remarkable that pollen from male catkins on an oak tree can be blown entirely randomly by the wind and received by a stigma inside a female flower on another oak tree tens of kilometres away.

DNA in the nuclei of oak trees is inherited equally from the mother (via an egg cell) and father (via the pollen). The chloroplasts of oak cells also contain some DNA, but this is inherited exclusively from the acorn-producing mother, as pollen contains no chloroplasts. Nuclear and chloroplast DNA can therefore be used to distinguish between male and female ancestry. Surprisingly, Q. robur and Q. petraea in northern Europe mostly have the same chloroplast DNA as each other, indicating common ancestry, but they show far more difference in the nuclear DNA inherited from their mother and father. A fascinating hypothesis has been proposed to account for this. After the last glaciation, Q. robur spread relatively rapidly northwards, dispersed by jays and other scatter hoarders to Scandinavia and the British Isles. Pollen from Q. petraea was then dispersed northwards, where it hybridised with Q. robur. This happened repeatedly, gradually converting some of the Q. robur population to Q. petraea. Over the generations, trees containing only nuclear DNA from Q. petraea developed, with adaptations for a different ecological niche from that of Q. robur. DNA in the chloroplasts of these trees was still of the Q. robur type.

In summary, it seems that Q. robur colonised northern Europe by dispersal of acorns, but the subsequent colonisation by Q. petraea was at least initially due to dispersal of pollen, resulting in gene introgression by hybridisation – a process that has been called cytoplasmic capture.

Further reading: Oak Origins, Andrew L. Hipp, The University of Chicago Press, 2024.

References:

1. Ashley, M.V. Answers Blowing in the Wind: A Quarter Century of Genetic Studies of

Pollination in Oaks. Forests 2021, 12, 575.

2. Hybridization as a mechanism of invasion in oaks, Rémy J. Petit, Catherine Bodénès, Alexis Ducousso, Guy Roussel and Antoine Kremer, New Phytologist (2003) 161: 151–164

1. What is wood and what is different about the wood of tulip tree?

The account that follows is based on a paper in the journal New Phytologist, published on 30th July 2024: https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19983

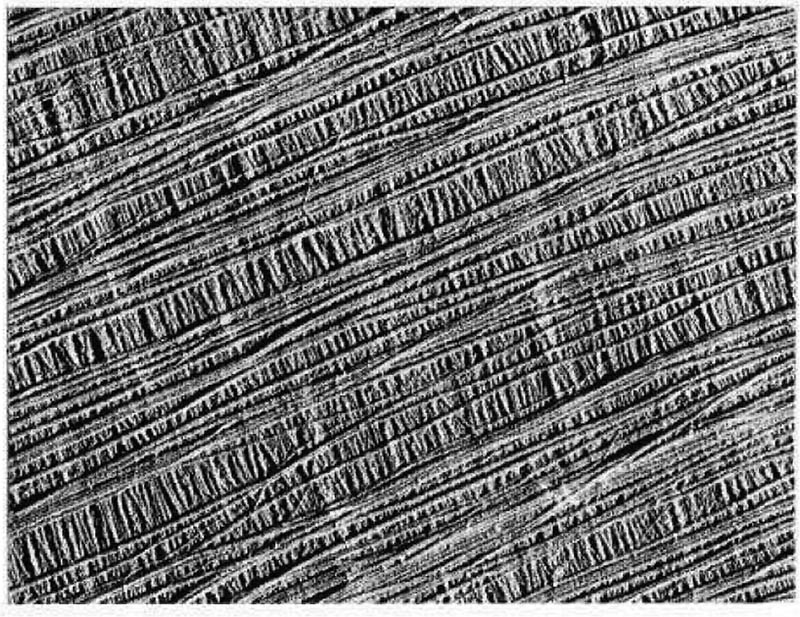

As every schoolboy knows, plant cells are surrounded by a cell wall. Cellulose is the principal component of these walls. Cellulose molecules are long, thin and have tensile strength. One molecule’s strength is limited, but cellulose molecules are cross-linked into groups known as microfibrils which are 3-4 nanometres in diameter. Microfibrils are glued together into macrofibrils by a complex carbohydrate called hemicellulose. There are many macrofibrils in a cell wall (visible in the electron micrograph below). Plant cells are typically pumped up to a high pressure like a bicycle tyre, but the strength of all the cellulose molecules in the cell wall prevents bursting.

When plants were becoming adapted to life on land during the Silurian period (430 or so million years ago) there several challenges, two of which were these:

* supporting aerial parts of the plant against gravity

* transporting water up to the aerial parts.

Both of these challenges were met by the evolution of xylem tissue with thickened cell walls composed of macrofibrils impregnated with lignin. These walls are very strong, so xylem can transport water under suction without imploding. Xylem also provides the support needed to resist gravity and avoid damage due to wind. Xylem is present in all conifers and flowering plants, but trees produce particularly large amounts. This is the wood that forms the centre of trunks and branches.

The diameters of cell wall macrofibrils in many different tree species have been measured in a recent research programme. A clear overall trend was found: gymnosperms such as pines, redwoods and cypresses have wider macrofibrils than angiosperms (flowering plants) such as oaks, limes and eucalypts. The average diameters were 26 to 29 nanometers versus 16 to 18 nanometers. However, trees in the genus Liriodendron were exceptional, with macrofibrils that were larger than all other angiosperms and smaller than those of gymnosperms. The average diameter for Liriodendron tulipifera was 22.4 nm and for Liriodendron tulipifera was 20.7 nm.

Liriodendrons diverged from other flowering plants 30 to 50 million years ago at a time when atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations declined from 1000 to 500 ppm. Liriodendron trees are very efficient absorbers of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. They store large amounts of carbon in compounds such as cellulose in the enlarged macrofibrils of xylem cell walls. Liriodendrons are therefore potentially very useful for carbon sequestration, so should be more widely planted. Liriodendron tulipifera grows to more than 55 metres tall and 3 metres in diameter in its native range from New England to Florida.

AJA © 16th September 2024

June 2025

comments from Peter Aspin concerning tree health.

In most years the main cause of shrub and tree deaths in this part of North Shropshire is late frost at a critical time of leaf emergence. With constant high pressure this spring the last ground frost was 18th May and last air frost several days earlier. However, this year something rather different has happened in that drowning appears to be the main causation of tree loss since much ground that has been supersaturated for the best part of eighteen months with tree roots constantly waterlogged and unable to “breathe”. This is especially apparent with hedgerow hollies in lower lying land or alongside watercourses, lengths of Leylandii hedge in similar positions and in my own case a fir (Abies Fabri). All evergreens. Also many Ash in the countryside appear to have very sparse canopies this spring and it will be interesting to see the long term effect of an extremely mild and wet winter followed by the driest spring for many decades.